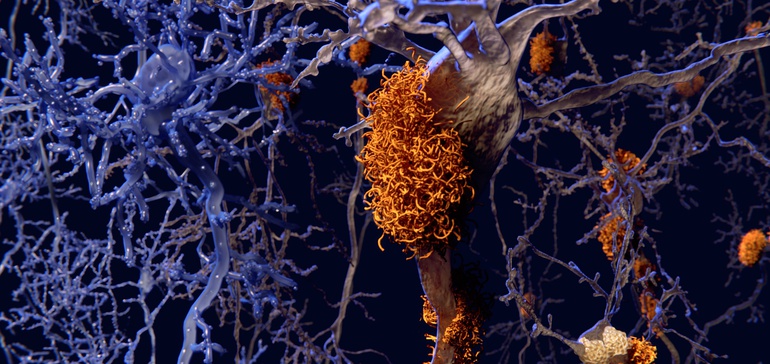

The plaques are considered hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease, formed in the brain from sticky clusters of a misfolded protein fragment called beta-amyloid.

For the past several decades, researchers and drugmakers alike have put faith in a tantalizing hypothesis that clearing these so-called amyloid plaques could lead to a treatment for the neurodegenerative condition.

Yet, time and time again, drugs designed to remove — or decrease production of — beta-amyloid have come up short in late-stage clinical testing. Each time, failure has come with qualifications, funneling hopes of a breakthrough onto the next advancing drug.

How to optimize your next drug’s performance in the real world

Only 14% of drugs that get to the phase of clinical trials eventually win approval from the FDA. Learn about top success factors for new drugs and suggested practical solutions for optimizing the drug development process.

Learn More

On Thursday, Biogen and Japanese partner Eisai disclosed the halting of two large Phase 3 studies testing aducanumab, an experimental therapy that had become the hypothesis’ standard bearer after successive setbacks for a half-dozen other anti-amyloid drugs in recent years.

Details were sparse, but an independent committee judged it unlikely aducanumab would meet its goal of slowing cognitive and functional impairment in patients with mild cognitive impairment or dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease.

By most accounts, past evidence showed aducanumab worked particularly well in clearing beta-amyloid. And Biogen and Eisai carefully designed the Phase 3 studies, enrolling only those patients who tested positive for beta-amyloid — a flaw of some earlier trials.

“This was the first really good experiment, the first really rigorous clinical trial to ask the question in a very careful way,” said Howard Fillit, a neuroscientist and chief science officer of the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation (ADDF). “And, apparently, it didn’t change the clinical course of the disease.”

Now, the question facing the field is what comes next. Other approaches, such as targeting another protein called tau, have some support, while the mid-stage Alzheimer’s pipeline looks more mechanistically diverse. Still, aducanumab’s failure could close a chapter on a period of drug development dominated by anti-amyloid research.

“At this point, we’ve done the right experiment and the hypothesis didn’t hold true,” said Fillit.

Not sufficient

Scientists have known about the toxic effects of amyloid build-up in organs for more than a century. Identification of beta-amyloid as the culprit in the amyloid plaques observed in Alzheimer’s patients is a comparatively more recent realization, first put forward in a 1984 paper.

Accumulation of beta-amyloid into plaques, the thinking went, could cause nerve cell toxicity and disrupt cell-to-cell communication in the brain.

In the ensuing years, beta-amyloid became the predominant focus of drugmaker efforts to develop an Alzheimer’s therapeutic. Despite that push, every anti-amyloid candidate has failed — a list of futility that has stretched into the hundreds.

In the past two years alone, Eli Lilly, Merck & Co., Johnson & Johnson, AstraZeneca and Roche have discontinued anti-amyloid drugs due to lack of benefit.

Faith in targeting amyloid has persisted, however, sustained by glimmers of potential benefit which led pharmaceutical companies to test therapies earlier in the course of the disease.

“Biogen has pushed the frontier to the earliest possible stage.”

Daniel Alkon

Chief Scientific Officer, Neurotrope

Development of diagnostics like positron emission tomography (PET) scans, meanwhile, allowed for more selective patient recruitment and raised hopes for greater chances at a trial success.

Biogen, for example, screened nearly 13,000 patients to enroll the 3,210 patients who participated in the two identical Phase 3 studies of aducanumab, dubbed ENGAGE and EMERGE.

By those measures, the anti-amyloid trials of the past several years represent the best test of whether specifically reducing amyloid plaques could deliver a cognitive or functional benefit.

“Biogen has pushed the frontier to the earliest possible stage; they’ve correlated it closely with amyloid, and it didn’t work,” said Daniel Alkon, who worked at the National Institutes of Health’s neurologic institute for 30 years and now serves as chief scientific officer at Neurotrope, a small biotech. “That’s telling us that this target is not going to be sufficient.”

Beta-amyloid is just one protein that can mis-fold in the brain. Others, such as tau or alpha-synuclein, could hold clues to deciphering how Alzheimer’s disease develops in the aging brain.

Tau, in particular, has intrigued, earning recognition as another characteristic mark of Alzheimer’s disease. Tangled clumps of the protein can stretch across regions of the brain, and its presence is correlated with worse cognition.

According to a recent count from the Cleveland Clinic, nine of the 36 experimental disease-modifying treatments currently in Phase 2 testing target tau. But tau’s seen failures as well, although it has been tested less rigorously than beta-amyloid.

“One antibody on one protein may not be enough,” said ADDF’s Fillit. “That’s the research question out there right now.”

Such thinking could translate to greater exploration of the role of inflammation in Alzheimer’s, or how the brain metabolizes energy.

“All avenues need to be pursued,” said Heather Snyder, a senior director at the Alzheimer’s Association, in an interview. “I think we’re seeing that reflected in the pipeline today — there are a variety of pathologies that need to be targeted as we learn more about the disease.”

A decade of research

Biogen’s investment into aducanumab did not come lightly.

The biotech licensed the rights to the compound from Swiss biotech Neurimmune in 2007, advancing what was then called BIIB037 into clinical testing.

Eight years later, in the spring of 2015, Biogen unveiled Phase 1b results from a study called PRIME, showing aducanumab led to significant reduction in amyloid plaque by PET scans as well as slower cognitive decline versus placebo.

Get biopharma news like this in your inbox daily. Subscribe to BioPharma Dive:

Email: email icon Sign up

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy. You can opt out anytime.

That study was the first positive finding from a group of patients who all tested positive for amyloid in the brain, noted Snyder. In past studies of anti-amyloid therapies, Snyder said, between 20% and 30% of individuals enrolled actually didn’t have beta-amyloid present in the brain.

“It’s a mark of the sluggishness in scientific progress that we’re testing products based upon 10-year-old technology.”

George Vradenburg

Cofounder, UsAgainstAlzheimer’s

Encouraged, Biogen quickly began Phase 3 testing of the drug, initiating ENGAGE and EMERGE just months after announcing the Phase 1b data.

Patients who were enrolled in either study received monthly intravenous infusions of aducanumab for more than a year and a half.

“Your heart has to go out to all of the people who put their life on hold and committed for a long period of time to monthly infusions,” said George Vradenburg, chairman and co-founder of UsAgainstAlzheimer’s, in an interview.

“This failure is on a personal level to them and, quite frankly, to the Biogen employees who for 10 years have been working on this product.”

Development of aducanumab has also come at significant expense for Biogen.

Over the past three years, Biogen — which partnered with Eisai on the drug in 2017 — has spent $743 million on developing aducanumab, or about 11% of the company’s entire R&D expenditures over that time period.

Relentless pursuit

While aducanumab’s failure puts the amyloid hypothesis in deeper doubt, clinical testing of anti-amyloid therapies won’t end with aducanumab.

As in the past, some will continue to keep the faith.

“In light of the overwhelming genetic, experimental, clinical and pathologic evidence accumulated over decades, it is clear that amyloid accumulation represents the first step in the disease process,” said Jim Kupiec, chief medical officer of ProMIS Neurosciences. Based in Canada, ProMIS is developing an anti beta-amyloid antibody.

“The amyloid hypothesis is valid. It simply needs to be revised as the amyloid oligomer hypothesis,” referring to a precursor form of the beta-amyloid plaques.

Among larger drugmakers, existing pipeline projects will likely continue to move forward, despite low expectations.

Indeed, one day after admitting defeat in ENGAGE and EMERGE, Biogen and Eisai announced enrollment had begun in a Phase 3 study testing BAN2401, an earlier-stage candidate that works similarly to aducanumab.

“Eisai and Biogen will continue our relentless pursuit toward finding a next generation disease modifying Alzheimer’s treatment,” the Japanese pharma said in a statement.

A late-stage trial of another Biogen and Eisai amyloid drug, elenbecestat, is nearing completion of enrollment, too.

Elsewhere, Roche has a beta-amyloid targeted therapy called gantenerumab in Phase 3, with results expected in 2022. Novartis is testing a drug designed to slow production of beta-amyloid in a late-stage trial as well.

Increasingly, though, those efforts may be grounded more in corporate calculations, and less scientific hope for an unexpected breakthrough.

“The decisions on whether to continue the amyloid [antibody] trials that are going on will probably be more business decisions rather than scientific decisions,” ADDF’s Fillit said.

One consequence of big pharma’s repeated failure with anti-amyloid therapies could be a greater push to explore other research areas of interest.

“You’re going to see some new names and some new methods of action being tested,” Vradenburg said.

“We’re continually hopeful that somebody out there still wants to win the Nobel Prize.”